Rhine water levels fall quickly next week, hampering barge trade

5 November 2021

Rhine water levels are likely to fall once again next week on a lack of rain in Western Germany, forcing barge operators to lighten loads to transport oil products up the Rhine.

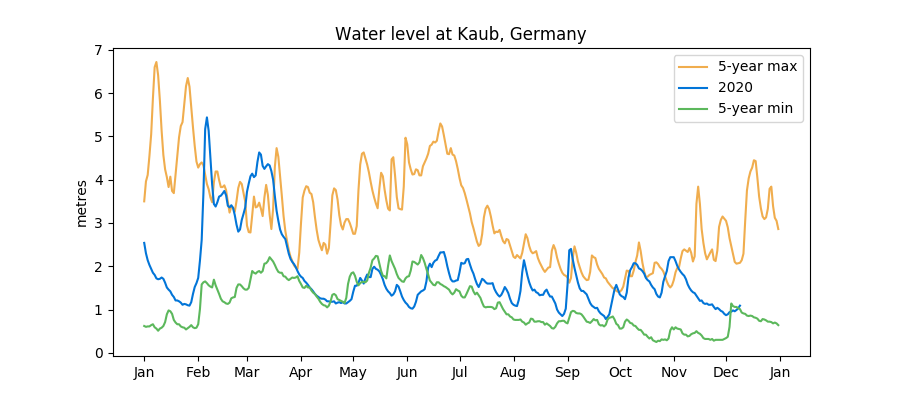

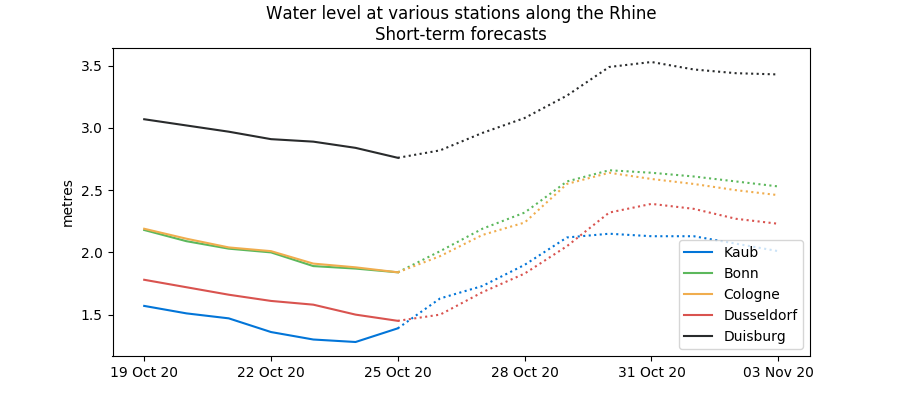

Passable water levels at Kaub in Germany, one of the narrowest stretches, will rise briefly to 1.13 metres on Monday, before falling to 0.87 metres by Sunday, November 14, data from German water authority WSV showed.

A typical 110-metre-long barge will only be able to carry around 900 mt of distillates rather than 2,500 kt to pass by Kaub by the end of next week.

Levels at the German town need to rise to 1.8 metres for barges to pass fully laden.

No substantial rain is expected over Germany over the coming days, forecast data showed, and October rainfall was below the five-year average for the second month in a row.

Rhine water levels briefly rise to relieve stress on ARA barge operators

3 November 2021

A heavy downpour of rain in Germany and Switzerland will cause water levels on the Rhine to rise until Monday, although they will drop lower again during the rest of next week, forecasts German water authority WSV said, allowing operators a window to increase the volume of oil products they can load on barges.

Passable water levels at Kaub in Germany, one of the narrowest stretches, will rise from 0.93 metres Wednesday to 1.35 metres by Monday before dropping back to 1.04 metres on Friday, November 12, WSV data showed.

ARA barge freights hit new highs Tuesday amid low water levels on Rhine

2 November 2021

Barge freight rates for transporting oil products in the trading hub around Rotterdam climbed Tuesday to extend a trend amid a shortage of vessels because of low water levels and a recent blockage on the Rhine, sources said.

Owners of barges are rushing to fulfill term contracts in Germany and Switzerland but can only partially load barges to make the journey from Amsterdam-Rotterdam-Antwerp, which is draining the number of barges available in the trading hub.

The freight rate for a standard 110-metre-long distillate barge between Antwerp and Amsterdam was up €0.20/mt Tuesday to €6.40/mt, according to brokers Riverlake.

Rhine re-opens to barge traffic after river dredged for three days

1 November 2021

The Rhine was re-opened to shipping on Saturday in a one-way channel between Iffezheim and Karlsruhe in Germany after authorities dredged the river for three days, according to sources and German authorities Monday.

The 25-kilometre stretch was blocked late last Tuesday after a container barge and a passenger boat were grounded after they swerved to avoid each other.

"The construction of an emergency channel for shipping near Hagenbach was completed...after three and a half days of dredging," said WSA Oberrhein in a statement.

Rhine closed after container and passenger barges were grounded

28 October 2021

A 25-kilometre stretch of the Rhine remains closed to shipping Thursday after a container barge and a passenger boat were grounded after they swerved to miss each other on Tuesday.

Very low water levels on the river, which is one of the main arteries for transporting oil products between ARA and Germany, are hampering operations to free vessels.

Falling Rhine water levels hampering barge traffic to Germany and Switzerland

25 October 2021

Barges carrying oil products will have to further lighten loads to travel along the Rhine this week as water levels on the river continue to fall, sources told Quantum, although heavy rain in Switzerland and Germany will cause water levels to rise again next week.

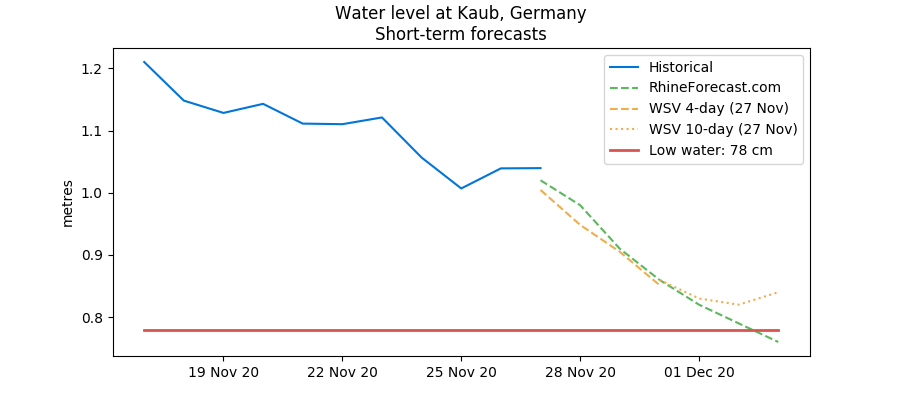

Levels at Kaub, one of the narrowest stretches in Germany, will fall to 0.83 metres by the weekend, down from 0.93 metres on Monday, according to WSV, Germany’s Federal Waterway Administration agency.

ARA barge freights costs rise again amid congestion at terminals

20 October 2021

Freight rates for transporting oil products in ARA nudged higher again Wednesday amid long waiting times and congestion at terminals in the trading hub, causing a scarcity of available barges to hire, brokers said Wednesday.

Rates from Rotterdam to Amsterdam or Antwerp rose to €4.90/mt, while rates between Antwerp and Amsterdam rose to €5.90/mt, both up €0.10 from Tuesday.

Freight rates for barges in ARA and along Rhine climb again

14 October 2021

Freights for transporting oil products in the trading hub in and around ARA as well as along the Rhine rose again Thursday on a combination of strong distillate demand, expectations of gasoline exports trans-Atlantic, and low water levels on the river, brokers reported Thursday.

The rate between Rotterdam and Antwerp for a standard distillate barge that can carry 2,500 mt rose was pegged at €4.60/mt, while the rate between Antwerp and Amsterdam was €5.60/mt, and between Flushing and Rotterdam was €4.80/mt – all gaining €0.10/mt from Wednesday, data from brokers Riverlake showed.

Rhine water levels continue to drop, logistical problems for operators

11 October 2021

Rhine water levels are likely to drop further over the next few days, data from Germany's Federal Waterways Agency showed Monday, forcing operators to only part-load vessels when transporting goods along Europe's most important waterway.

At Kaub, near many of Germany's industries, water levels are likely to fall from 1.18 metres Monday to 1.10 metres by 16 October and 1.06 metres by 20 October.

Barge freight rates in ARA continue to rise

5 October 2021

Freight costs for transporting oil products in ARA have risen again Tuesday amid a scarcity of available barges, according to brokers Riverlake Tuesday.

The rate for hiring a 2,500 mt middle distillate barge from Rotterdam to Amsterdam or Antwerp was pegged at €3.60/mt, up €0.20/mt from Monday.

Rhine barge freights for oil products continue to rise

30 September 2021

Barge freights rates for transporting oil products from Rotterdam into Germany and Switzerland along the Rhine surged higher Friday to extend gains this week amid low water levels, according to brokers Riverlake.

Freight rates from Rotterdam to Karlsruhe, home to the 320,000 bpd Miro refinery, Germany’s largest refinery, have risen to €16.50/mt ($19.10/mt) for a standard middle distillate barge, up from €15/mt Wednesday and from €13.50/mt on Monday.

Rhine barge freight rates for oil products jump amid low water levels

28 September 2021

Barge freights rates for transporting oil products from Rotterdam into Germany and Switzerland along the Rhine surged higher Tuesday amid low water levels, according to brokers Riverlake.

Operators are having to lighten loads to make the journey.

Rhine fully re-opens to barge traffic

23 July 2021

The Rhine has fully re-opened to barge traffic Friday after water levels dropped through the week, sources said.

Water levels at Maxau, one of the deepest sections, dropped to 7.45 metres Friday, below the ‘Mark II’ level that had prevented sailing, according to brokers Riverlake.

Rhine still closed from Speyer

20 July 2021

The Rhine remained closed between Speyer and Maxau in Germany Tuesday, but floodwater levels are continuing to subside, according to barge brokers Riverlake.

Water levels by the Miro refinery near Karlsruhe are expected to fall under the Mark II level, which allows sailing on the river again, from Friday night.

Levels at Maxau, near Karlsruhe, will fall from 8.16 metres Tuesday to 7.8 metres on Friday, according to Riverlake’s amalgamation of three agency forecasts."

Rhine closure narrows to 76.5 km stretch in Germany, gasoil diffs steady

19 July 2021

Just 76.5km of the Rhine in Germany is still closed to shipping as water levels start to subside from the devastating floods last week, a spokesperson from the waterways authority WSA Rhein told Quantum.

"At the moment, the Rhine is closed for shipping only between Iffezheim (km 334) and Mannheim-Rheinau (km 410,5)," said Florian Krekel.

"The stretch between Mannheim-Rheinau and the German-Dutch border is open."

"The weather forecast is dry over Germany for the rest of the week, and water levels are expected to continue to fall, easing fears of greater disruption on one of the key arteries for refined oil product trade."

Rhine water levels still rising Saturday

17 July 2021

Rhine water levels were still rising Saturday with significant disruptions likely on extensive stretches of the river this weekend, forecast data from Germany’s Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration (WSV) showed.

But the water levels are expected to subside from Monday and the Rhine is likely to fully re-open for traffic by the middle of next week, the forecast data showed and sources told Quantum Friday.

Rhine closed for barge traffic until next week after devastating flooding

16 July 2021

The Rhine is likely to re-open for traffic by the middle of next week, sources told Quantum Friday, after the banks burst Thursday causing devastating flash floods and at least 58 deaths in southern Germany.

High water levels have created “Marke II” levels along the river, which means sailing along the river has been stopped.

Rhine depth levels at Cologne in Germany were pegged at 7.6 metres Friday and will remain around the same levels in three days’ time, according to Riverlake’s amalgamation of three agency forecasts.

Barge traffic stopped on Rhine in Germany after river levels swell

15 July 2021

Barge traffic on the upper Rhine beyond Speyer in Germany has stopped and the stoppage could be extended as far down the river to Dusseldorf on Friday because of high water levels, brokers warned Thursday.

There could also be disruption to traffic in the Netherlands with a chance the Limmel lock on the river Mass could be closed Thursday.

Severe flooding of Rhine river likely to hit barge flow by end of week

13 July 2021

Parts of the Rhine, Europe’s most important river for transporting energy products and commodities, are likely to reach severe flood status by the end of the week, helped by significant rainfall over Western Europe and in a very unusual development for the time of year.

Temporary navigation restrictions are likely to be triggered on a stretch of the river from Kaub to Cologne, known as the Middle Rhine, according to forecast data from Germany’s Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration.

Rain forecast indicates Rhine in danger of hitting flood levels

5 July 2021

The Rhine, Europe’s most important river for transporting energy products and commodities, could reach near flood status by 12-13 July, data from Germany’s Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration (WSV) showed Monday.

The river is expected to swell over the coming days, helped by plentiful rainfall over Germany and Switzerland and late snowmelt in the Alps.

Rhine water levels surge allowing healthy flow of barge traffic

25 June 2021

Rhine water levels have surged once again due to high rainfall in parts of Germany and Switzerland and continued snowmelt in the Alps, data from Germany’s Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration (WSV) showed Friday.

At Kaub, near many of Germany’s industries, water height reached 3.2 metres Friday, up from around 2.4 metres on 21 June. This is the third such increase in water levels since the middle of May, the WSV data showed.

New wave on Rhine to boost maximum tonnage for barges

8 June 2021

Depth levels on the river Rhine are forecast to rise this week, enabling oil product barges to carry more tonnage, according to brokers Tuesday.

Levels around Kaub in Germany, one of the narrowest stretches of the river, will rise from 2.57 metres Tuesday to 3.27 metres by Friday, according to shipbroker Riverlake, citing three sources for its forecast.

Rhine swells after heavy rain

24 May 2021

Rhine water levels have risen to their highest in three months following heavy rainfall in western Europe, data from Inerrijn Group shows Monday.

At Kaub, a key chokepoint near many of Germany’s industries, depth levels have reached 3.2 metres, up from 2.6 metres on 18 May and the highest since a flood in early February.

Rhine water levels to surge with rainfall

18 May 2021

Water levels on the Rhine, Europe’s second-longest river used to transport many commodities, are due to surge over the next few days, helped by above-average rainfall.

At Kaub, a key chokepoint near many of Germany’s industries, water height was 2.6 metres at the time of writing, near the top of the five-year range for the time of year.

Barge restrictions expected on Rhine as water levels drop

26 April 2021

Rhine water levels have fallen consistently in the second half of April and barges may need to be lightened by the end of the month, forecasts show.

At Kaub, a key chokepoint situated near many of Germany’s industries, water levels are expected to fall below 1 metre on 29 April, triggering restrictions for barges operating on the river.

Rhine to reach flood level by the weekend

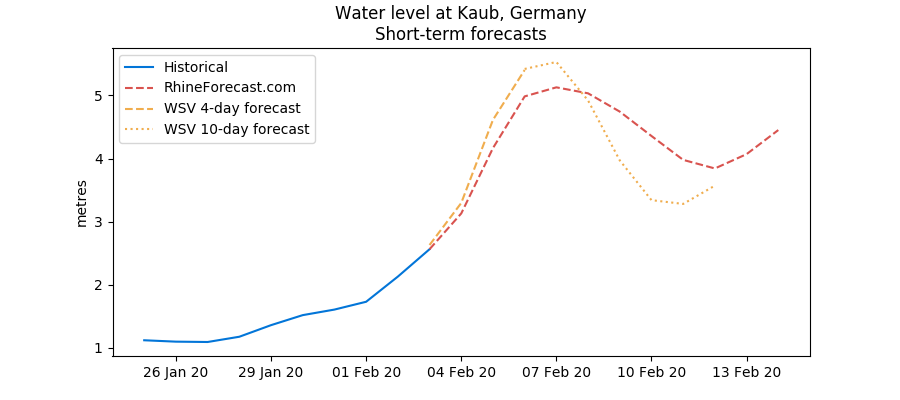

27 January 2021

The Rhine river is about to reach its first flood situation of the year due to very high rainfall in Germany and Switzerland.

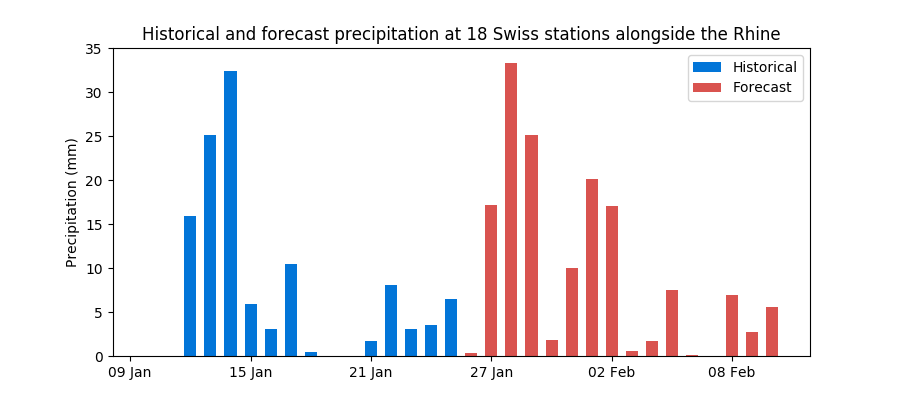

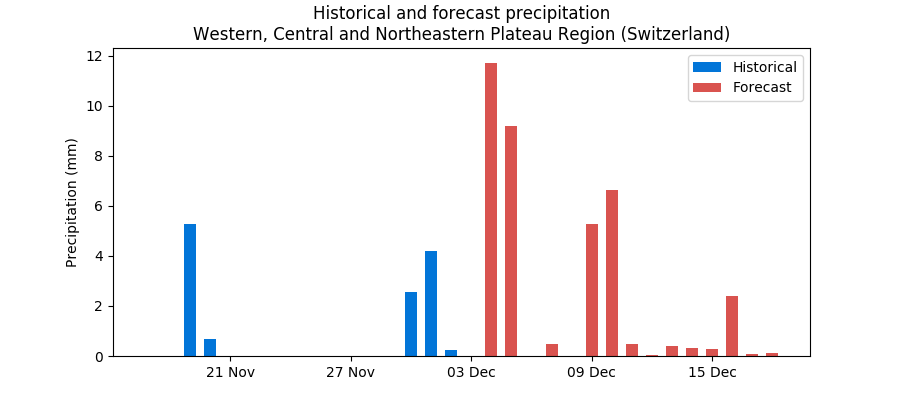

At the beginning of the year, river levels were still hovering close to their five-year minimum, but steady rainfall since the middle of January has changed all that. Precipitation at stations situated close to the river has averaged 2.6 millimetres per day so far this month, more than double last year’s total and above the five-year average of 2.1 millimetres.

The situation is similar in Switzerland, where the Rhine originates, with precipitation averaging 4.6 millimetres this month, more than three times as much as in January 2020.

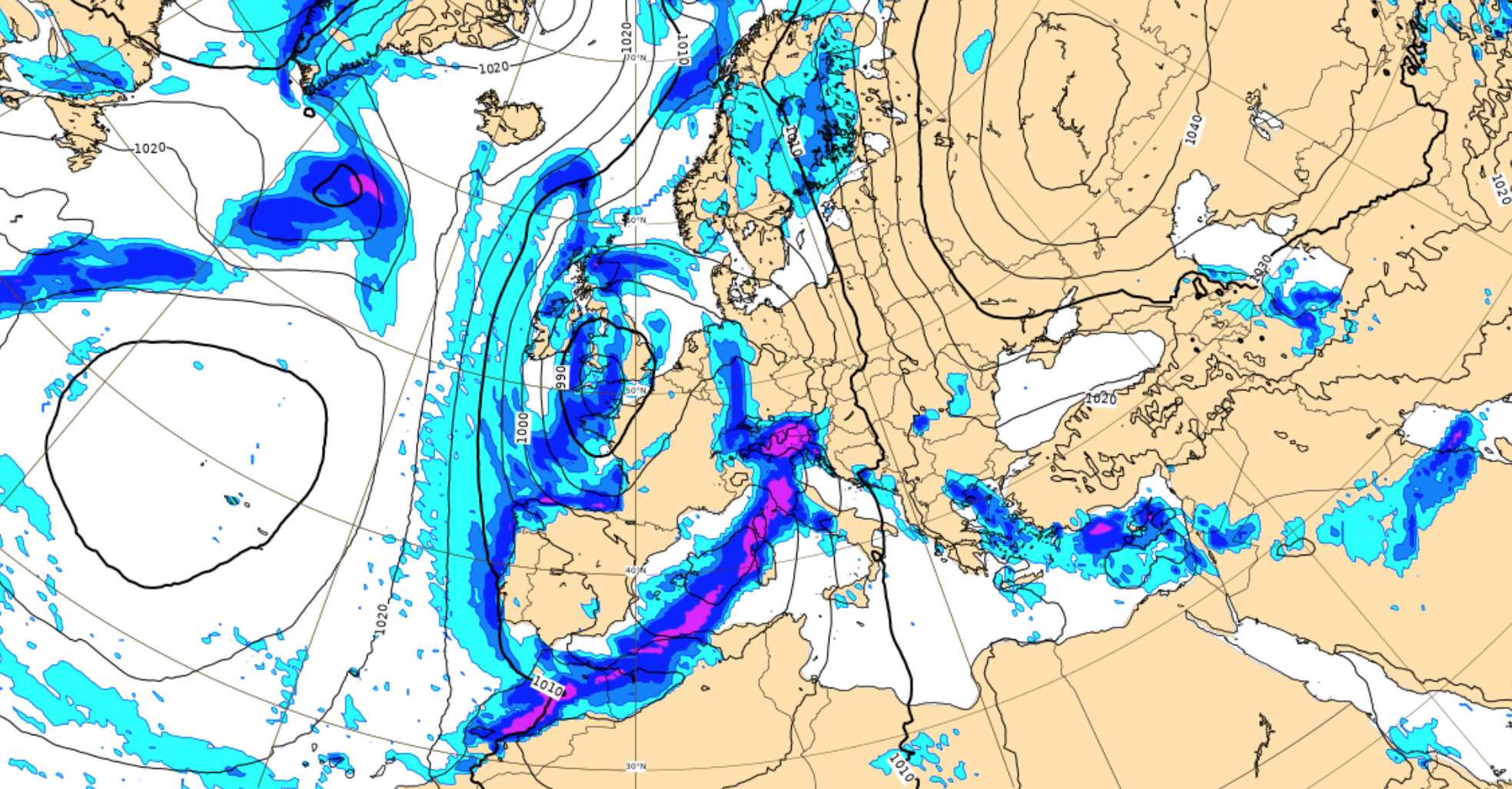

Very high rainfall is forecast over the next few days, thus tipping the Rhine into flood territory. In Switzerland, it will rain between 15-20 millimetres on Wednesday 27 January, more than 30 millimetres on Thursday and around 25 millimetres on Friday.

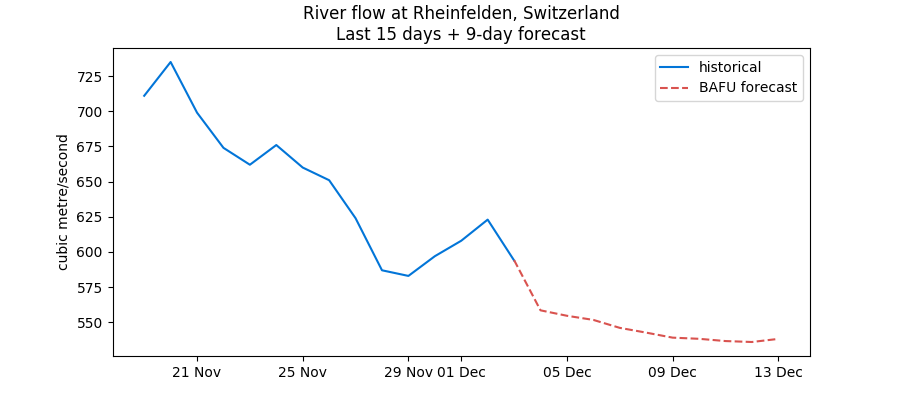

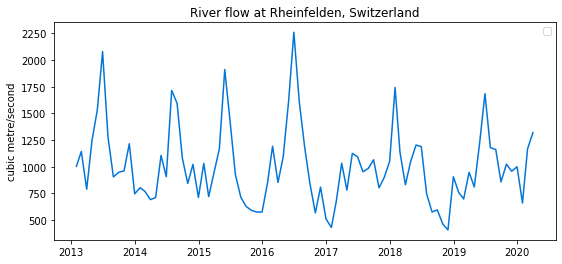

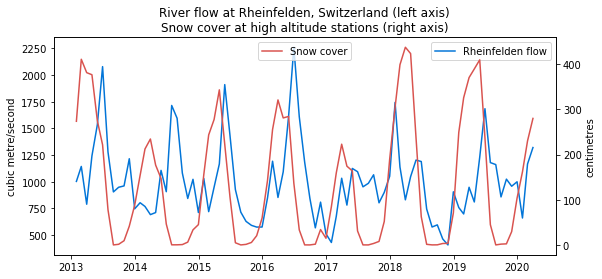

These are exceptional totals seen only a couple of times a year. As a result, river flows at Rheinfelden, near the border between Switzerland and Germany, are expected to more than double in just a few days to 2,200 cubic metres per second by Friday.

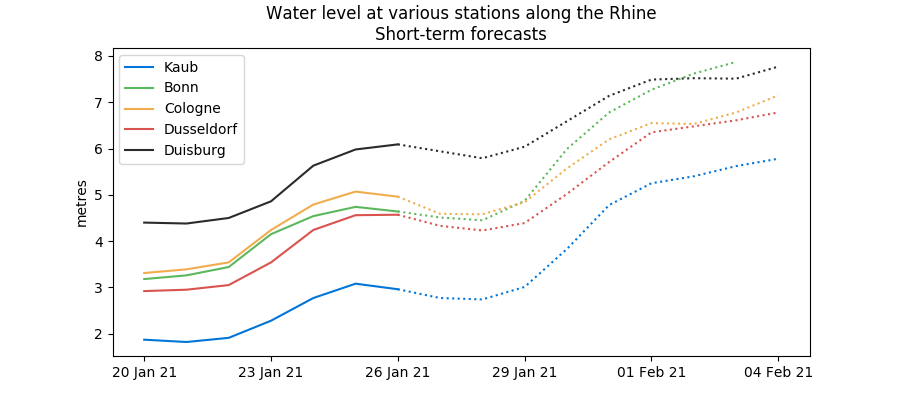

We expect water levels at Kaub, near Germany’s industries, to rise from 3 metres to 5.5 metres by Monday 1 February, above the high water threshold of 4.6 metres. Further down the river, water height could reach 6 metres in Dusseldorf, 7 metres in Bonn and nearly 8 metres in both Cologne and Duisburg.

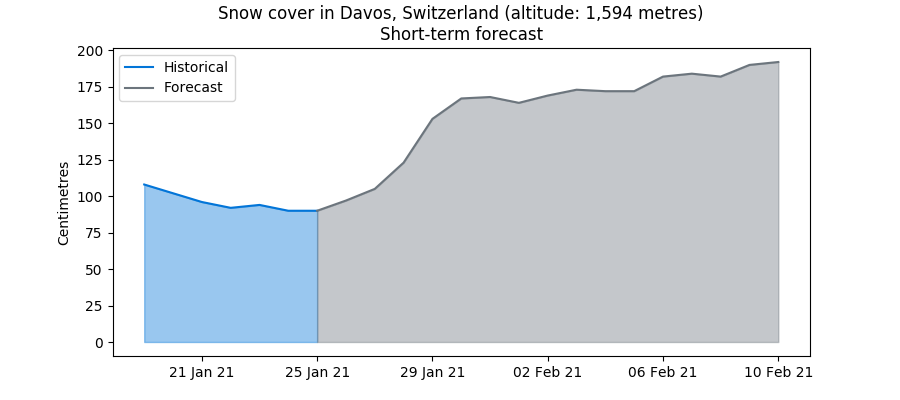

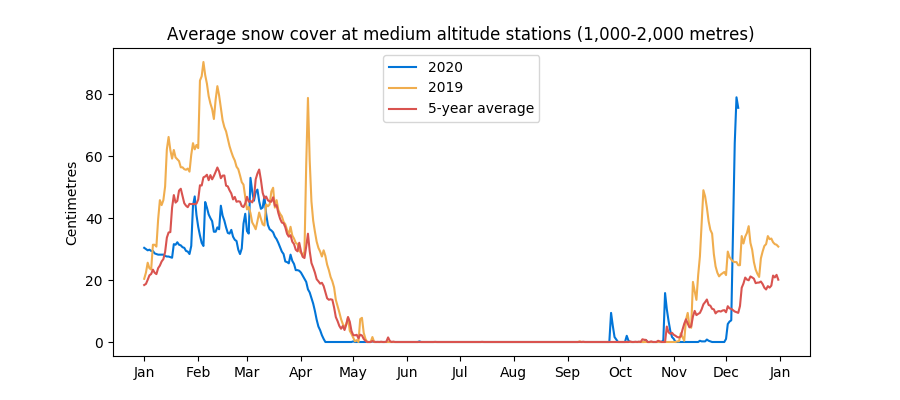

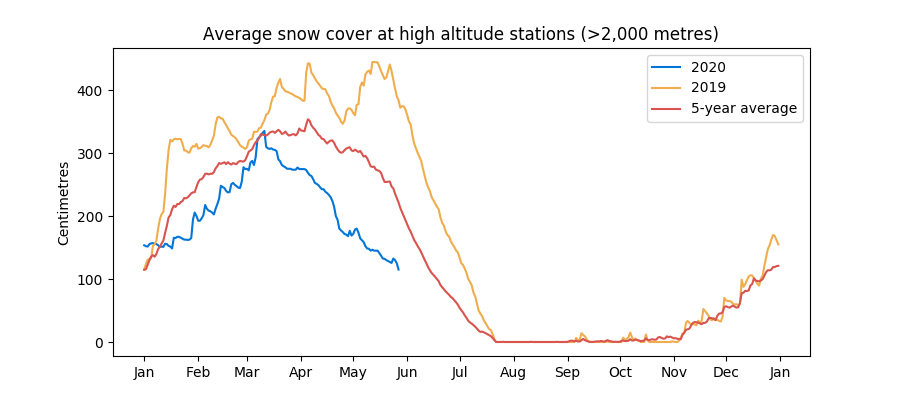

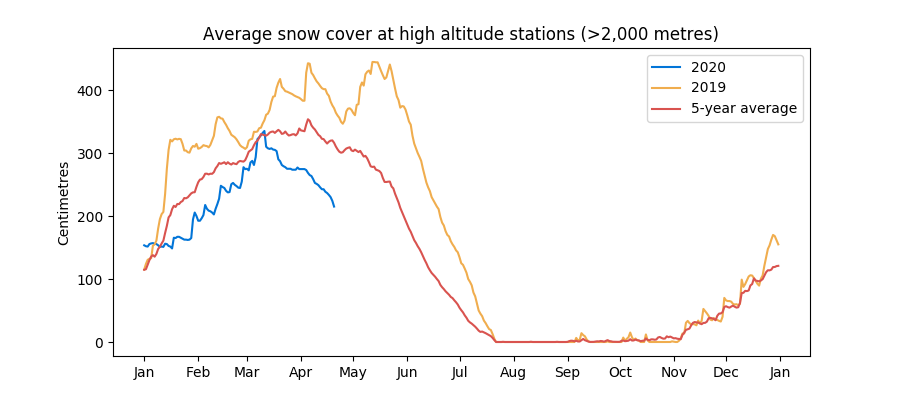

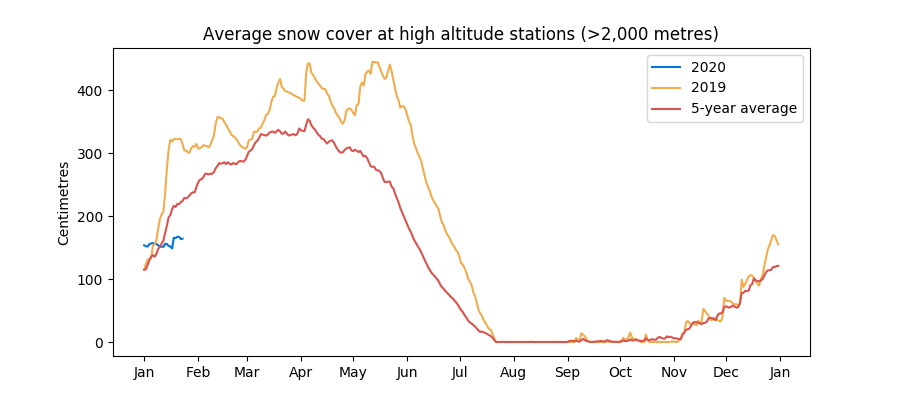

Plentiful precipitation, together with the cold weather recorded over the last few weeks, has also boosted snow levels in the Alps. At high altitude stations, above 2,000 metres, snow levels are almost 1 metre above last year’s total at the same time and only slightly below 2019 levels.

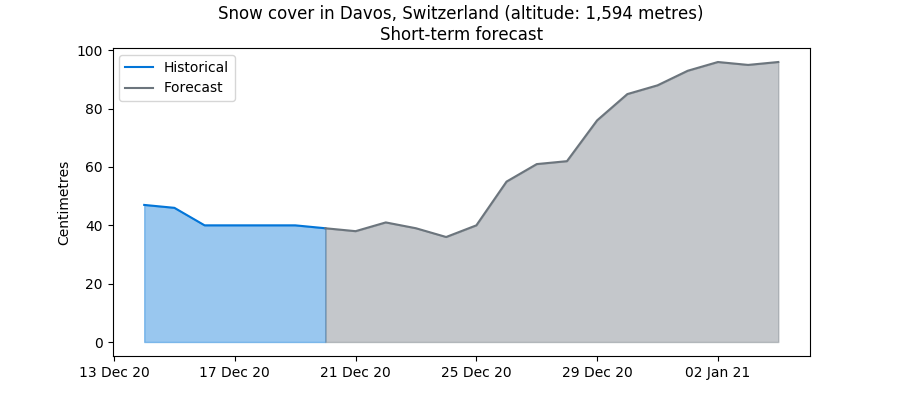

At medium-altitude stations, between 1,000 and 2,000 metres of altitude, there is the most snow recorded in at least 10 years. What’s more, taking the Swiss stations of Davos as a barometer, we expect snow totals to almost double between now and the beginning of February, which would be truly exceptional.

All of this means that the Rhine is likely to be well fed in the spring, when snow melts with higher temperatures. But, for now, barge operators need to focus on the here and now, as the flood situation is likely to trigger restrictions in several locations. Good luck with it all.

Rhine water levels to finish year on a high note

22 December 2020

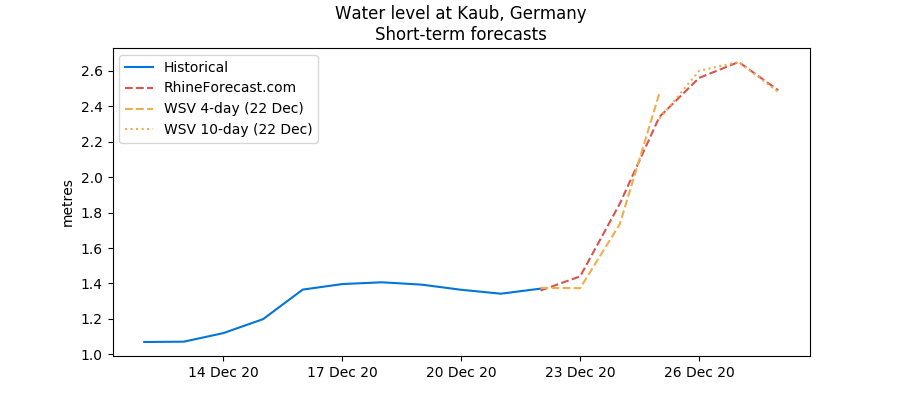

Water height on the Rhine is likely to finish the year at comfortable levels, after languishing near its five-year minimum for most of the past month.

At Kaub, near many of Germany’s industries, water levels will rise sharply from 1.4 metre at the time of writing to about 2.5-2.6 metres on 26 December.

It will rain substantially over the next few days over both Germany and Switzerland. Temperatures are quite warm for the time of year, thus ensuring that snow cover remains limited.

In Davos, Switzerland, snow cover is about 40 centimetres right now and is expected to rise from 25 December onwards to 1 metre at the beginning of 2021, helped by much colder weather. These figures are from a snow height model I built over the last few weeks, using daily historical weather data from 1930 onwards. It will be the subject of my next blog.

In the meantime, I wish you all a merry Christmas and a happy new year.

Rhine water levels likely to remain low in December

10 December 2020

Rhine water levels remain close to their lowest levels in five years, despite moderate rainfall recorded over the last few days.

It will take more substantial rain to move them up and, for now, it isn’t coming. So far in December, rainfall along the middle section of the Rhine has been largely in line with seasonal normals. There is a bit of rain in the forecast over the coming days, but not enough to compensate for a particularly dry November (See blog post from 27 November).

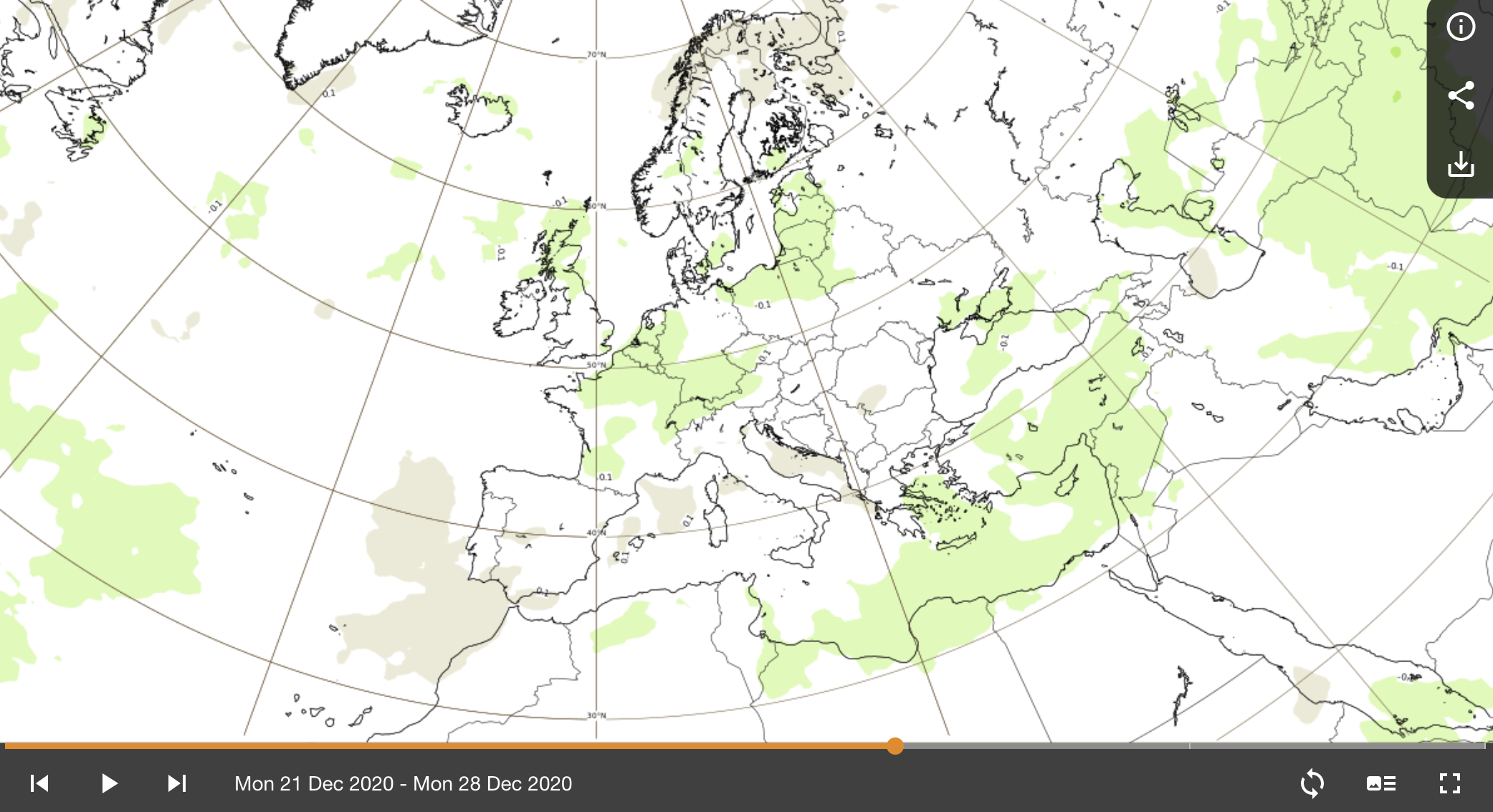

The ECMWF, which issues weather forecasts 10-42 days out, continues to expect a drier than normal December in Germany and Switzerland.

In the Swiss mountains, snow levels are high for the time of year, following last weekend's storm. This is especially true at between 1,000 and 2,000 metres of altitude, where there is currently up to 80 cm of snow. At higher altitudes, snow levels remain below the five-year average, due to a mild start of the season.

First snowfall of the season

5 December 2020

The first substantial snowfall of the 2020-21 winter season took place on Friday 4 December and is set to continue into the weekend.

A low pressure system centered over the Mediterranean has directed a mass of cold and humid air towards the Swiss mountains, with snow expected at between 500-800 metres above sea level, according to MeteoSwiss. Above 1,000 metres, in the Western Alps, there could be as much as 30-40 cm of snow.

Up to 9 mm of precipitation is expected over the Western, Central and Northeastern Plateau Region on Saturday, but given the freezing weather, it will turn into snow rather than rainfall, and will thus not flow directly into the Rhine.

The Rhine river's flow at Rheinfelden, near the German border, is actually expected to ease over the coming days.

Further downstream, Rhine water levels have stopped falling, helped by rainfall (the same mass of humid air that created snow over Switzerland). But the outlook for December hasn't changed much since last week's blog post: rain is not currently expected to be plentiful over the coming weeks.

Driest November in 10 years brings Rhine to low water threshold

27 November 2020

My latest blog, written on 26 October, speculated that "if seasonal patterns hold, rain should be even more plentiful in November and water levels should be supported." Well, that turned out to be completely false.

With the benefit of hindsight and as there remain just a few days until the end of the month, November will enter the history books as the driest in 10 years.

It has rained just 0.8 mm/day on average at stations along the Rhine. This is less than half the level recorded in November 2019 and is actually less than was recorded over the summer in Europe - in a month that is supposed to be the third or fourth wettest of the year!

Needless to say, this has had a huge impact on the Rhine, with water levels falling steadily in the last few weeks. At Kaub, water levels are just above 1 metre at the time of writing and are likely to fall to around 80 cm in a few days, thus nearly breaching the official low water threshold of 78 cm for the location. This means more pain for barge operators, who must incorporate these restrictions into their operational plans.

Rain is likely to remain elusive in the early part of December, thus prolonging the pain for everybody. And, though highly speculative at this stage (given that weather forecasts become unreliable after 10 days), the ECMWF 10-42 day forecasts do not point towards a very wet December either.

Rainy autumn keeps Rhine well fed

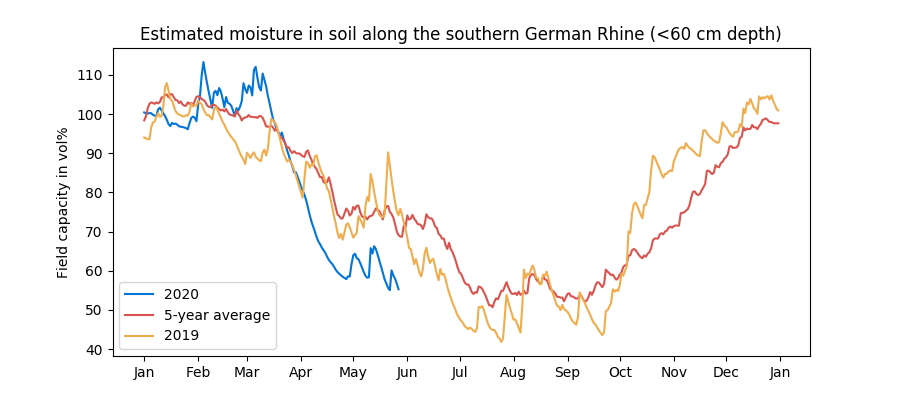

26 October 2020

Rhine water levels are surging amid rainy weather, the fourth such bounce registered since the end of summer in Europe.

Rain has kept water levels reasonably high this autumn and mostly above the five-year average. Soil moisture readings along the river are back to normal levels, after being consistently in drought territory.

This is in stark contrast with the spring and summer periods when water levels were constantly low due to hot and dry weather. It has rained around 2.4 mm per day on average so far during October, above the five-year average of 1.8 mm.

If seasonal patterns hold, rain should be even more plentiful in November and water levels should be supported.

For now, we expect Kaub water levels to increase to above 2 metres by the end of October, allowing normal navigation all along the river. We’ll need more rain in November to maintain these levels, but what’s clear is that a rainy autumn has mostly staved off the threat of very low water levels for the rest of this year.

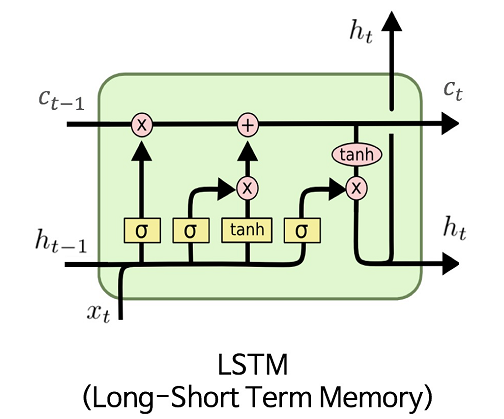

Using machine learning to predict Rhine water levels

15 September 2020

Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) models are a powerful type of neural network ideally suited to predict time-dependent data. Rhine water levels fit right into this category: they vary over time, depending on a range of variables such as rain, temperatures and snow cover in the Alps.

The Rhine is Europe’s lifeblood. For centuries it has been used as a major artery for shipping goods into Germany, France, Switzerland and Central Europe. However, with climate change, water levels on the river are likely to become more variable. Forecasting the river's level accurately is therefore a primary concern for a whole range of actors, from shipping companies to commodity traders and industrial conglomerates.

Unlike classical regression-based models, LSTMs are able to capture non-linear relationships between different variables; more precisely, the sequence dependence among these variables. This blog focuses on the problem of Rhine river forecasting using LSTMs, rather than the theory behind these models.

Problem at hand

The problem we are looking to solve here is the following: we would like to forecast next-day water levels at Kaub, a key chokepoint in western Germany, with the highest possible accuracy.

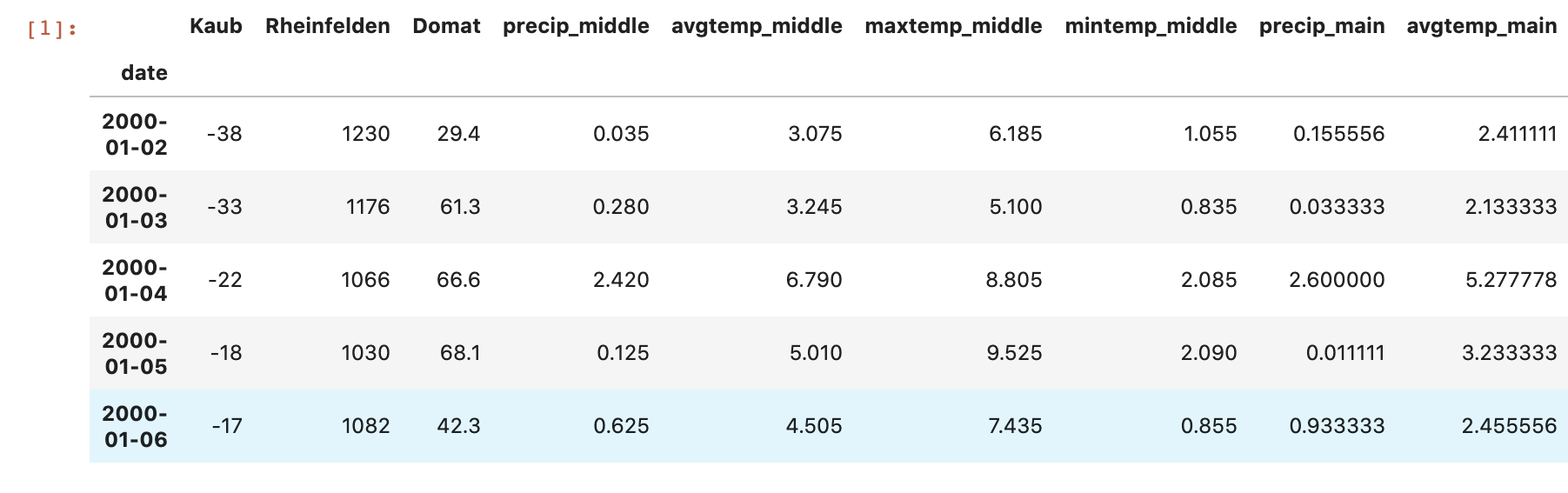

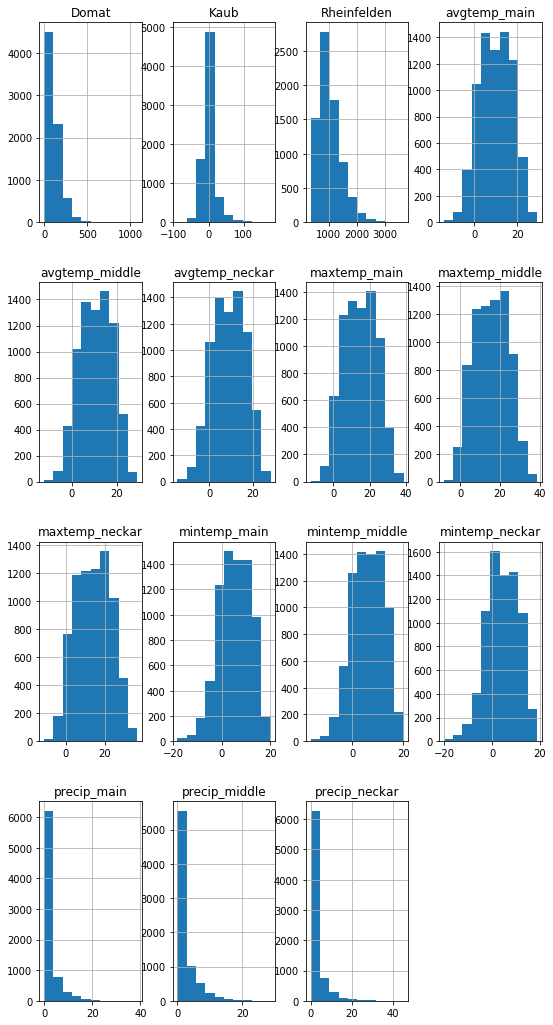

We have historical daily data from 2 January 2000 to 27 July 2020, equivalent to 7513 observations. The dataset includes 15 different categories, displayed as columns:

- ‘date’: the date of the observation

- ‘Kaub': the day-on-day difference in Kaub water level, in centimetres - this is the ‘y’ value we are trying to forecast (source: WSV)

- ‘Rheinfelden': the absolute value of the water flow at Rheinfelden, in Switzerland, in cubic metres per second (source: BAFU)

- ‘Domat': the absolute value of the water flow at Domat, near the source of the Rhine, in cubic metres per second (source: BAFU)

- ‘precip_middle': the average daily amount of rain recorded at 20 weather stations along the Rhine, in millimetres (source: DWD)

- ‘avgtemp_middle': the average temperature recorded at the same stations, in degrees Celsius

- ‘maxtemp_middle': the maximum temperature recorded at the same stations

- ‘mintemp_middle': the minimum temperature recorded at the same stations

- ‘precip_main’: the average daily amount of rain recorded at 8 weather stations along the Main, a major tributary of the Rhine, in millimetres (source: DWD)

- ‘avgtemp_main’: the average temperature recorded at the same stations, in degrees Celsius

- ‘maxtemp_main’: the maximum temperature recorded at the same stations

- ‘mintemp_main’: the minimum temperature recorded at the same stations

- ‘precip_neckar’: the average daily amount of rain recorded at 7 weather stations along the Neckar, also a major tributary of the Rhine, in millimetres (source: DWD)

- ‘avgtemp_neckar’: the average temperature recorded at the same stations, in degrees Celsius

- ‘maxtemp_neckar’: the maximum temperature recorded at the same stations

- ‘mintemp_neckar’: the minimum temperature recorded at the same stations

Note that the choice of variables is entirely mine and is based on my experience dealing with Rhine analysis. Selecting the right inputs is one of the most important steps in time series analysis, whether you are using classical regression models or neural networks. If you select too few variables, the model may not capture the full complexity of the data (this is called underfitting). By contrast, if you choose too many inputs, the model is likely to overfit the training set. This is bad as well as it could mean the model struggles to generalise to a new dataset, which is essential for predictions.

First, let’s load all the libraries we will need for this exercice:

import datetime

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import tensorflow as tf

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

import joblib

Below is a sample of the first few lines of the dataset. We can load it easily with the Pandas library:

# first, we import data from excel using the read_excel function

df = pd.read_excel('RhineLSTM.xlsx')

# then, we set the date of the observation as the index of the entire dataframe

df.set_index('date', inplace=True)

df.head()

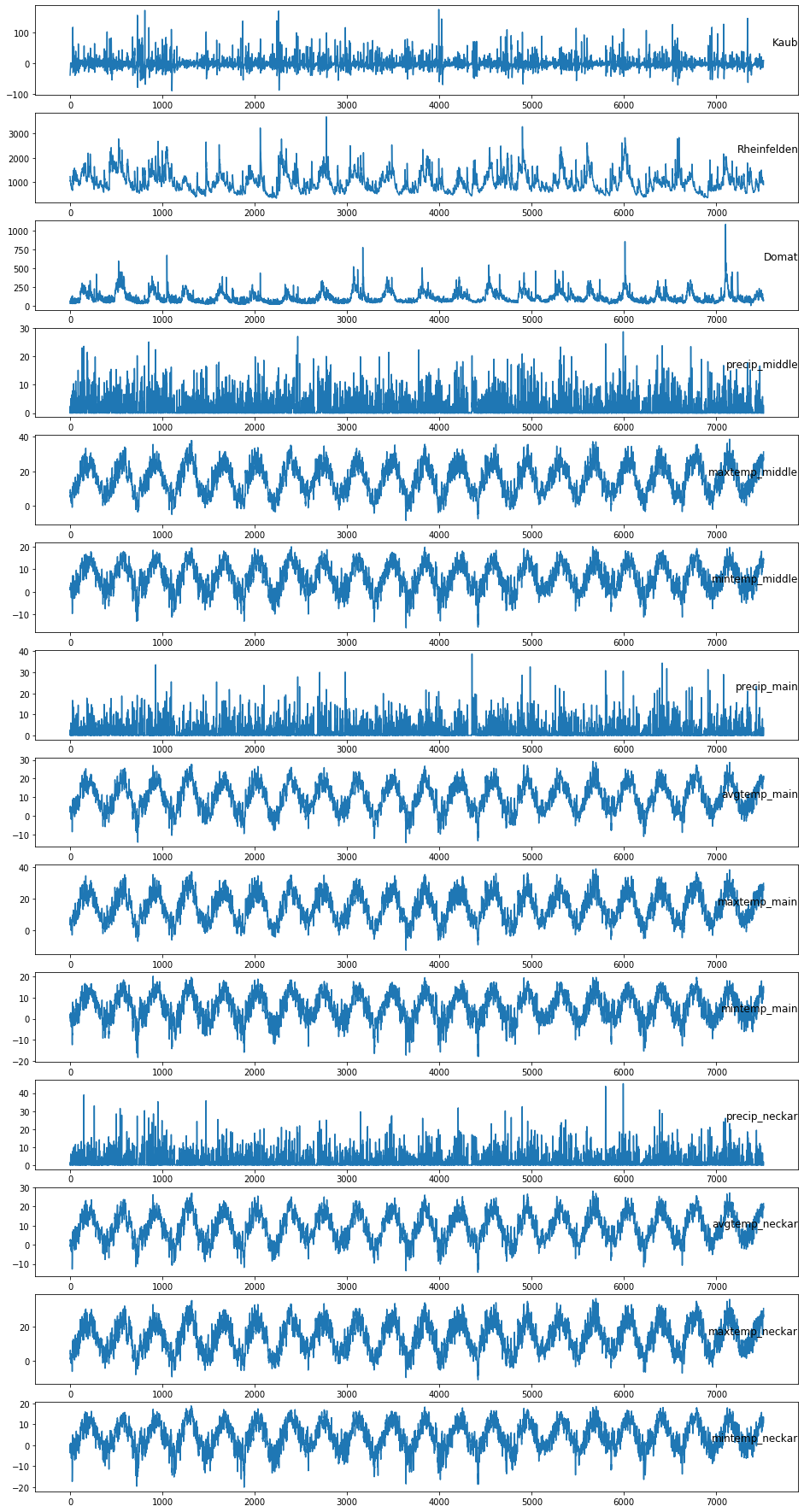

Once loaded, we can plot the dataset using the Matplotlib library:

# specify columns to plot

columns = [0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

i = 1

values = df.values

# define figure object and size

plt.figure(figsize=(9,40))

# plot each column with a for loop

for variable in columns:

plt.subplot(len(columns), 1, i)

plt.plot(values[:, variable])

plt.title(df.columns[variable], y=0.5, loc='right')

i += 1

plt.show()

It’s also generally a good idea to plot histograms of the variables:

# histograms of the variables

df.hist(figsize=(9,18))

plt.show()

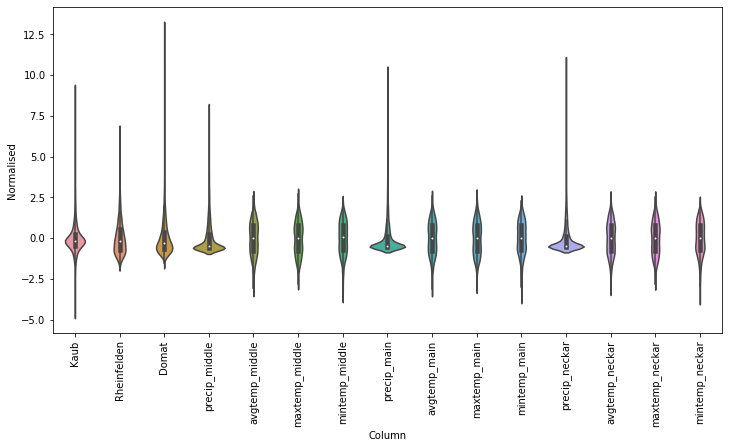

Using the Seaborn library, you can create a violin plot to understand the distribution of each variable:

# calculate dataset mean and standard deviation

mean = df.mean()

std = df.std()

# normalise dataset with previously calculated values

df_std = (df - mean) / std

# create violin plot

df_std = df_std.melt(var_name='Column', value_name='Normalised')

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

ax = sns.violinplot(x='Column', y='Normalised', data=df_std)

_ = ax.set_xticklabels(df.keys(), rotation=90)

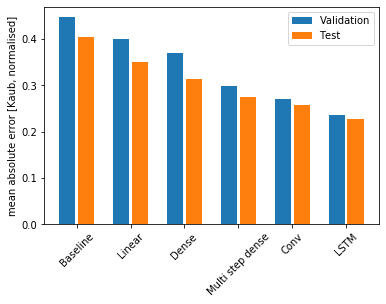

Evaluating different models

I have trained different types of models on the Rhine dataset to establish which one fits best:

- The baseline model, also known as persistence model, returns the current rate of change in Kaub water level as the prediction (essentially predicting a constant rate of change from one day to the next). This is a reasonable baseline as Rhine water levels typically change over a number of days due to wider weather phenomena (eg, slow melt in the Alps progressively making its way downstream).

- The simplest model you can train assumes a linear relationship between the input variables and the predicted output. Its main advantage over more complex models is that it is easy to interpret, however it performs only marginally better than the baseline network.

- A dense network is more powerful, but cannot see how the input variables are changing over time. This shortcoming is addressed by multi-step dense and convolution neural networks, which take multiple time steps as input for each prediction.

- The LSTM model comes out on top, with a lower mean absolute error rate on the validation and test sets.

The Python code required to create this chart is too long for this blog, but you can access it here, applied to a different dataset.

LSTM model for regression

LSTM networks are a form of recurrent neural network that can learn long sequences of data. Instead of neurons, they are made of memory blocks connected to each other via layers. A memory block contains gates (input, forget, output) that manage its state and output, and enable it to be smarter than a typical neuron.

They have been used extensively in academic circles to forecast river height and have been proven to outperform classical hydrological models in certain situations.

Let’s start all over again with the code from the beginning of this article to load the Rhine database:

import datetime

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import tensorflow as tf

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

import joblib

# first, we import data from excel using the read_excel function

df = pd.read_excel('RhineLSTM.xlsx', sheet_name='Detailed4_MAIN’)

# then, we set the date of the observation as the index of the entire dataframe

df.set_index('date', inplace=True)

Data preparation

To build a functioning LSTM network, the first (and most difficult) step is to prepare the data.

We will frame the problem as predicting today’s rate of change in Kaub water level (t) given the weather and Swiss upstream flows of today and the previous 6 days (backward_steps = 7).

The dataset is standardised using the StandardScaler() function in the Scikit-Learn library. For each column of the dataframe, each value in the column has the mean value subtracted, and then divided by the standard deviation of the whole column. This is a pretty ordinary step for most machine learning models and allows the whole network to learn faster (more on this below).

Then, the dataframe is passed through a transformation function. For each column, we create a copy of each of the previous 7 days’ values (15 * 7 = 120 columns). The shape of the resulting dataframe is 7506 rows x 120 columns.

# load dataset

values = df.values

# ensure all data is float

values = values.astype('float32')

# normalise each feature variable using Scikit-Learn

scaler = StandardScaler()

scaled = scaler.fit_transform(values)

# save scaler for later use

joblib.dump(scaler, 'scaler.gz')

# specify the number of lagged steps and features

backward_steps = 7

n_features = df.shape[1]

# convert series to supervised learning

def series_to_supervised(data, n_in=1, n_out=1, dropnan=True):

n_vars = 1 if type(data) is list else data.shape[1]

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

cols, names = list(), list()

# input sequence (t-n, ... t-1)

for i in range(n_in, 0, -1):

cols.append(df.shift(i))

names += [('var%d(t-%d)' % (j+1, i)) for j in range(n_vars)]

# forecast sequence (t, t+1, ... t+n)

for i in range(0, n_out):

cols.append(df.shift(-i))

if i == 0:

names += [('var%d(t)' % (j+1)) for j in range(n_vars)]

else:

names += [('var%d(t+%d)' % (j+1, i)) for j in range(n_vars)]

# put it all together

agg = pd.concat(cols, axis=1)

agg.columns = names

# drop rows with NaN values

if dropnan:

agg.dropna(inplace=True)

return agg

# frame as supervised learning

reframed = series_to_supervised(scaled, backward_steps, 1)

Define training and test datasets

We must split the prepared dataframe into training and test datasets to allow a fair evaluation of our results. The training dataset represents 80% of our values and we will use the remaining 20% for evaluation. As we are dealing with data ordered through time, it is a very bad idea to shuffle the dataset, so we keep it as is. Next, we reshape our training and test datasets into three dimensions for later use.

# split into train and test sets

values = reframed.values

threshold = int(0.8 * len(reframed))

train = values[:threshold, :]

test = values[threshold:, :]

# split into input and outputs

n_obs = backward_steps * n_features

train_X, train_y = train[:, :n_obs], train[:, -n_features]

test_X, test_y = test[:, :n_obs], test[:, -n_features]

print(train_X.shape, len(train_X), train_y.shape)

# reshape input to be 3D [samples, timesteps, features]

train_X = train_X.reshape((train_X.shape[0], backward_steps, n_features))

test_X = test_X.reshape((test_X.shape[0], backward_steps, n_features))

print(train_X.shape, train_y.shape, test_X.shape, test_y.shape)

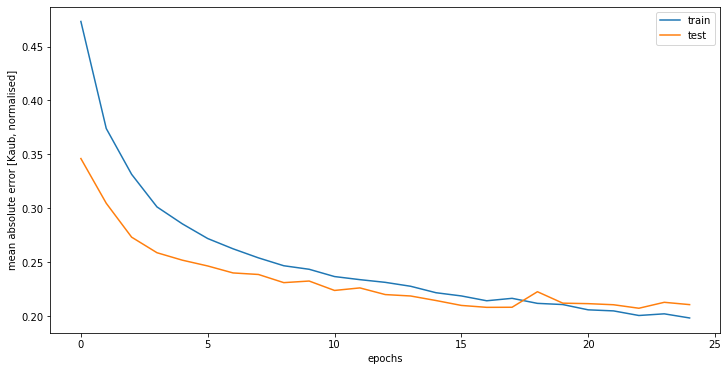

Fit model

Finally, we are able to fit our LSTM network. Thanks to the TensorFlow/Keras library, this only requires a few lines of code. I have chosen to fit 64 memory blocks in batch sizes of 72. I use the Adam optimisation algorithm, which is more efficient than the classical gradient descent procedure.

# design network

model = tf.keras.models.Sequential()

model.add(tf.keras.layers.LSTM(64, input_shape=(train_X.shape[1], train_X.shape[2])))

model.add(tf.keras.layers.Dense(1))

model.compile(loss='mae', optimizer='adam')

# define early stopping parameter

callback = tf.keras.callbacks.EarlyStopping(monitor='loss', patience=3)

# fit network

history = model.fit(train_X, train_y, epochs=25, callbacks=[callback], batch_size=72, validation_data=(test_X, test_y), verbose=2, shuffle=False)

# plot history

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

plt.plot(history.history['loss'], label='train')

plt.plot(history.history['val_loss'], label='test')

plt.ylabel('mean absolute error [Kaub, normalised]')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

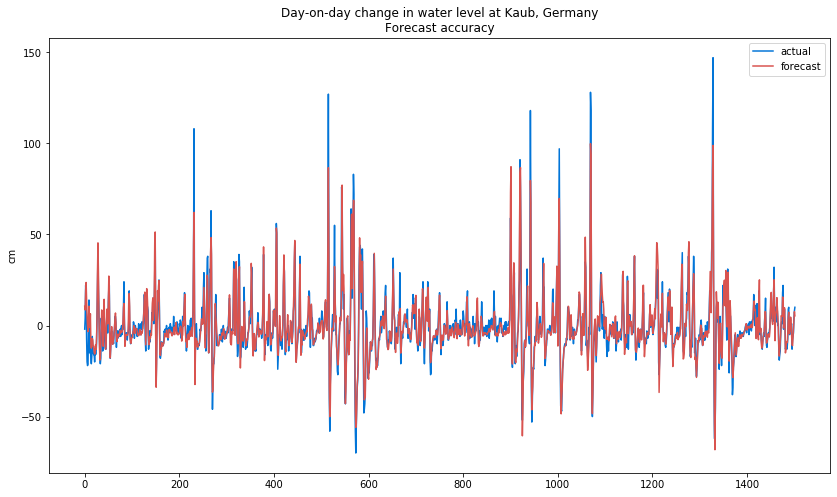

Model results

After the model is fit, we can launch the forecast and invert the scaling to obtain our final results. We can then calculate an error score for the model. Here, the model achieved a root mean squared error (RMSE) of 6.2 centimetres, which is good but can probably be improved on.

# make a prediction

yhat = model.predict(test_X)

test_X = test_X.reshape((test_X.shape[0], backward_steps*n_features))

# invert scaling for forecast

inv_yhat = np.concatenate((yhat, test_X[:, -(n_features - 1):]), axis=1)

inv_yhat = scaler.inverse_transform(inv_yhat)

inv_yhat = inv_yhat[:,0]

# invert scaling for actual

test_y = test_y.reshape((len(test_y), 1))

inv_y = np.concatenate((test_y, test_X[:, -(n_features - 1):]), axis=1)

inv_y = scaler.inverse_transform(inv_y)

inv_y = inv_y[:,0]

# calculate RMSE

rmse = np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(inv_y, inv_yhat))

print('Test RMSE: %.3f' % rmse)

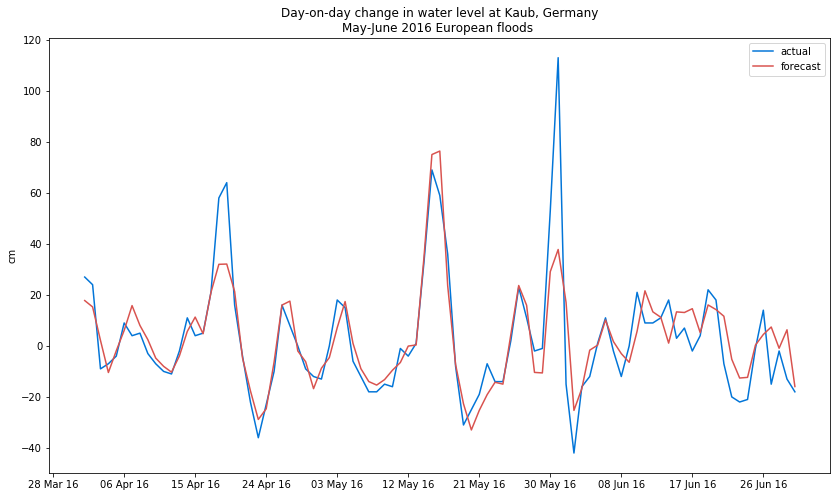

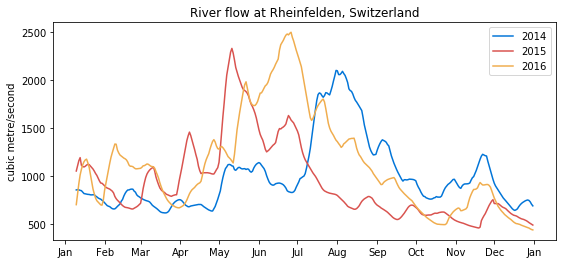

I have also checked the model's performance during extreme weather events, such as the extensive floods recorded in Europe in May-June 2016 which caused more than Eur1 billion of damage in Bavaria alone. The model was generally able to track the rise in water levels, however during two particular peaks (one in mid-April and the other in early June) it gave low figures.

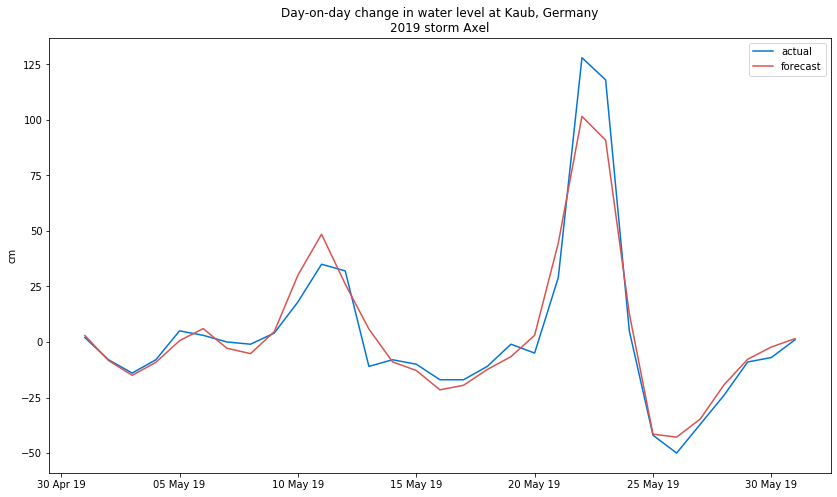

The trained LSTM network also performed well during storm Axel, in May 2019, which caused a very rapid rise in water height of more than 1 metre on two consecutive days. Once again, however, it gave slightly lower estimates than actual figures when floods peaked.

In both cases, I suspect the low figures are due to one major Rhine tributary, the Moselle, which was left out of the analysis for lack of reliable meteorological data. The Moselle joins the Rhine at Koblenz, just north of Kaub. This is a possible area of improvement in future.

Model performance

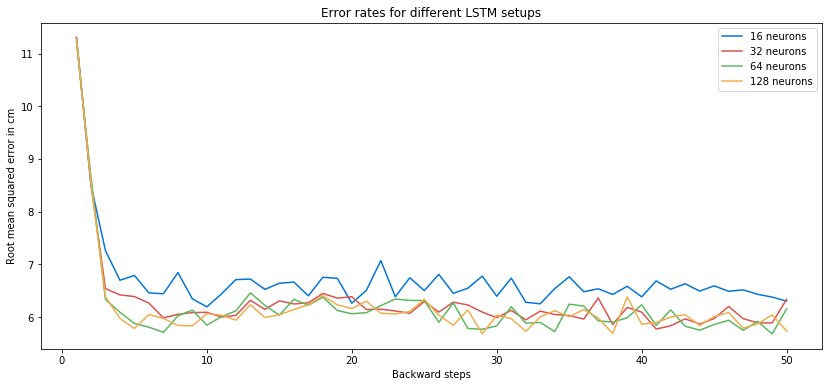

Finding the best hyperparameters is one of the most important (and time-consuming) tasks in machine learning. I ran many different versions of the network in order to find the best possible setup:

- Pre-processing: For those familiar with Scikit-Learn, I found the StandardScaler() to be more suitable for the Rhine dataset than the MinMaxScaler(), which normalises all values to between 0 and 1. Normalising values with the MinMaxScaler() gave erratic performance. A quick look at the histograms plotted at the beginning of this blog post indicates that most of the Rhine input variables follow a Gaussian distribution, so this is logical.

- Backward steps: I found 7 days to be a reasonable time frame for weather analysis and given the time required for water to flow down the Alps. There is no meaningful improvement in the model's performance by increasing the steps beyond this figure.

- Neurons: Small networks of 16 memory cells perform less well, but larger networks of 32 neurons and beyond are fairly similar. I picked 64 memory cells for my model.

- Epochs: I have chosen to stop training once the algorithm has gone through the dataset 25 times. Beyond this threshold, performance begins to plateau and the model starts to overfit the training set.

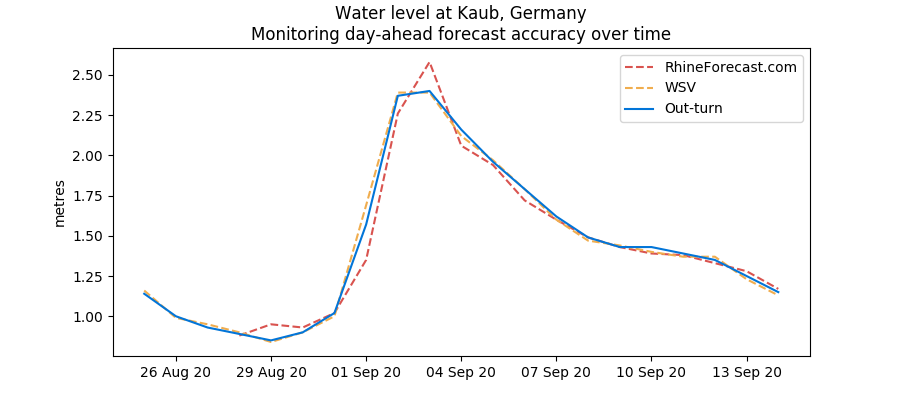

I have deployed a version of this model online. Its performance can be monitored here.

I’ll try to improve this model in future by adding/removing variables and tweaking hyperparameters further. If you have any thoughts, don’t hesitate to get in touch with me.

Rhine water levels to surge in early September

31 August 2020

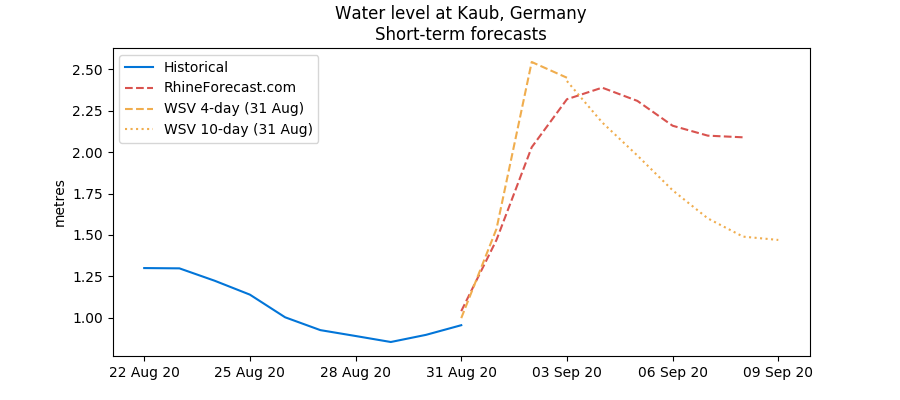

Water levels on the Rhine river are likely to more than double in the space of just a few days in early September as a result of higher upstream flows from the Swiss Alps and higher rainfall.

Kaub levels fell below the 1 metre threshold in late August to their lowest level since the 2018 drought. This followed a scorching summer in Western Europe that saw temperatures reach 40 degrees Celsius on some days.

Water levels on the Rhine river are likely to more than double in the space of just a few days in early September as a result of higher upstream flows from the Swiss Alps and higher rainfall.

We forecast Kaub water levels to reach nearly 2.4 metres on 3-4 September. The WSV is even more bullish, predicting 2.5 metres on 2-3 September. Heavy rainfall in Switzerland is to blame.

Flows at Rheinfelden, near the Swiss/German border, have gone up from 800 cubic metres/second on 29 August to nearly 1,200 cubic metres on 30 August and will reach 1,800 cubic metres today, on 31 August.

However, this surge will be just that without more rainfall over the next few weeks. The WSV expects Kaub levels to fall back to 1.5 metres on 9 September, although this forecast is still subject to weather changes.

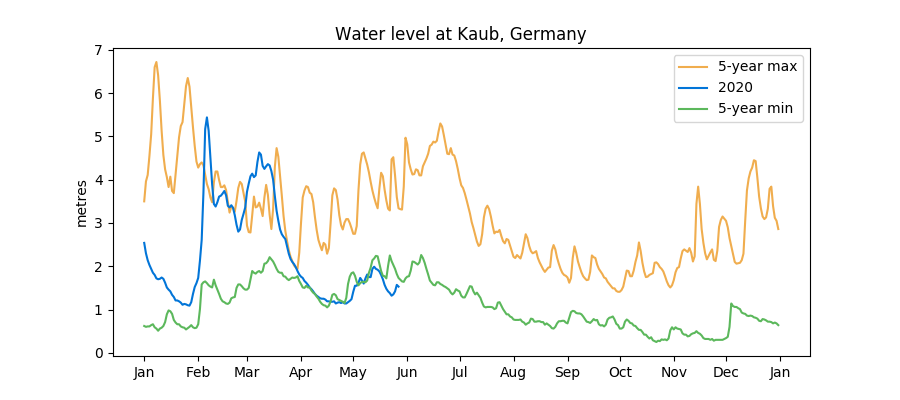

Rhine water levels hit 5-year seasonal low

28 May 2020

Water levels on the Rhine are hovering around their lowest level in five years for the time of year. They’ve been at the bottom of the five-year range since the start of April and do not show any signs of recovering meaningfully in the short-term.

The main reason has been the persistent lack of rain along with higher-than-normal temperatures in Switzerland and southern Germany, which has kept underground reservoirs dry. Soil moisture along the southern section of the Rhine is well below both last year’s figure and the five-year average. And this is before the summer season begins in Europe.

Another contributing factor has been the relatively poor snow season in the Alps. Warm temperatures over April and May have depleted what was already a shallow snow cover going into the spring. Snow cover below 2,000 metres in the Swiss Alps was all gone in mid-April, around two weeks earlier than usual. And snow cover at higher altitudes is just above 1 metre at the time of writing, compared with 4 metres at the same time last year.

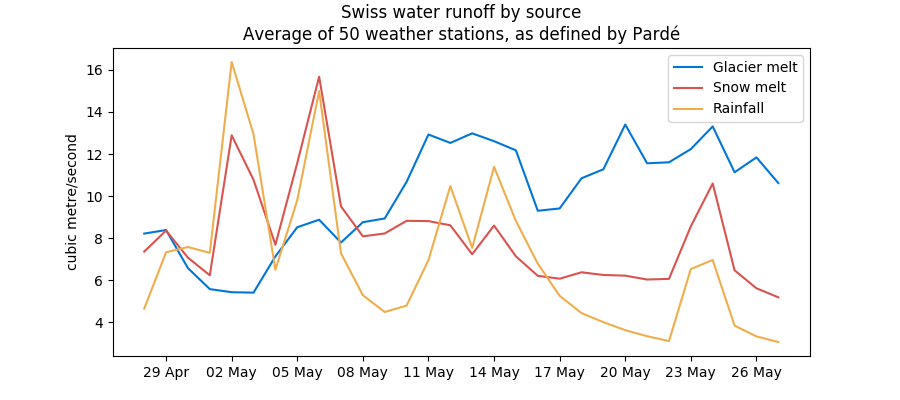

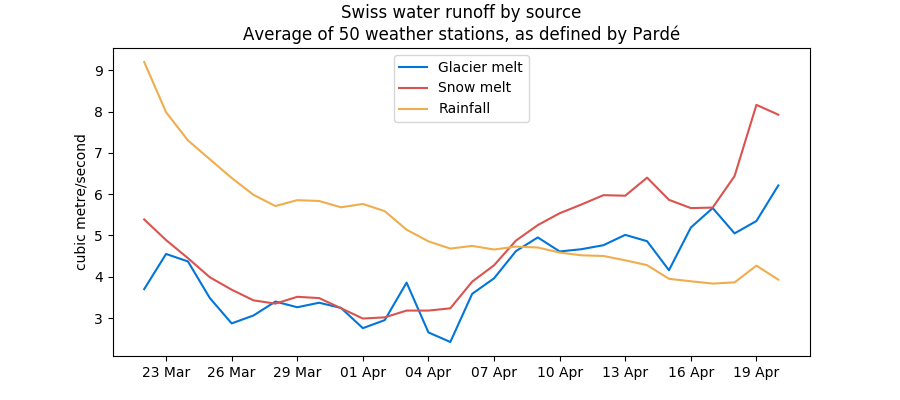

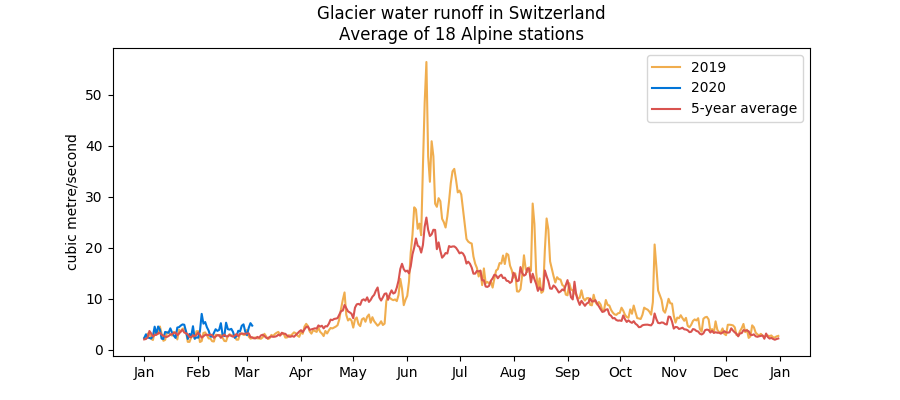

In fact, glacier melt has been the main source of upstream run flow since the start of May, overtaking both snow melt and rainfall.

All this means that the Rhine is living on borrowed times and could fall below the critical 1-metre threshold if no rain comes. This website forecasts Rhine water levels to rise a little in early June together with rain, but that is still subject to uncertainty and could easily be reversed later in June.

Some relief for the Rhine with rain on the way

28 April 2020

It rained about 3 mm today in Northeastern France, Western Germany and Switzerland, and more is coming over the next few days. As the forecasts stand, it could rain substantially over the weekend of 2-3 May, with about 13-14 mm on each day.

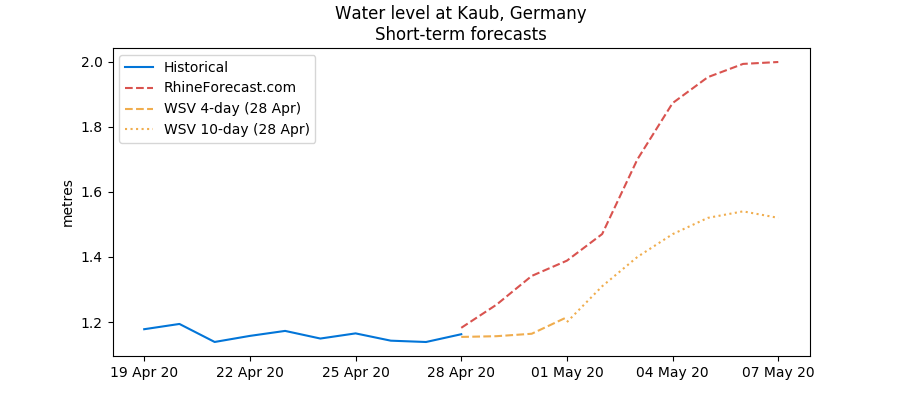

This should be enough to bolster Rhine water levels, which have hovered around the low end of the five year range since the beginning of April. At Kaub, a key chokepoint, they were just 1.2 metres today, not enough for barges to circulate fully loaded.

This blog forecasts Kaub water levels to reach nearly 2 metres by 7 May, helped by rising Swiss upstream flows (themselves the result of a combination of precipitation and snow melt) and rain in Germany and France. Germany’s Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration forecasts water levels of 1.5-1.6 metres by that date.

I don’t know for sure why our figures differ by 50 centimetres. It could be because the WSV uses weather forecasts that show less rain than me, and/or because our coefficients differ for April and May (ie, the same amount of rain triggers a higher water level in my model than in theirs).

But, in any case, the pattern is clear and water levels are going to rise. May is typically 60% rainier than April in southern Germany, even if it is far too early to know if that will be sustained later in May. In addition, as I explained in my blog published last week, more snow from the Alps is likely to melt, which will feed the river.

All in all, we are therefore unlikely to test the recent lows on the river, barring a drastic change in the weather.

Driest April in 13 years pushes Rhine to very low levels

21 April 2020

The coronavirus is upsetting the world around us, but amid the furore it can be easy to miss important phenomena.

Where I’m sitting in Paris, we’ve had almost no rain so far in April. This is borne out by weather data showing that, at 0.4 mm per day on average so far this month, April is proving to be the driest month along the Rhine since April 2007.

This has had important implications for river levels, which are at their lowest (for the time of year) in five years. At Kaub, a key chokepoint, the river was just above 1 meter at the time of writing, not enough for barges to circulate fully loaded.

With many of Europe’s key industries closed and energy demand in freefall amid the coronavirus pandemic, these restrictions may not be so visible. But if they last, they will be a thorn in the foot when businesses reopen in May.

I’m not too worried about the next few weeks, however, as we’re right at the beginning of the snow melting season in the Alps. As you can see from the chart below, snow melt became the biggest provider of water to the river on 7 April and will no doubt continue to increase seasonally in line with temperatures.

However, given the relatively poor snow season during the winter of 2019-20 (a consequence of very mild temperatures), snow levels are not high enough to sustain the river much beyond the first half of June.

For this reason, we need rain, or it will be a scorching summer on the Rhine.

Breaking down the upper Rhine's seasonality

5 March 2020

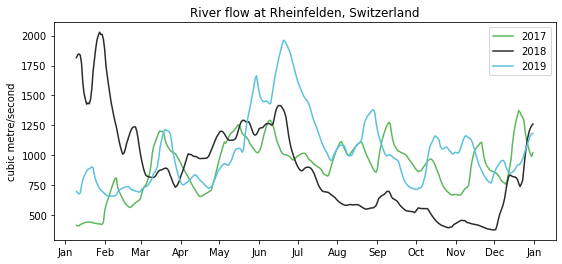

The Rhine river goes through annual peaks and troughs. In the chart below, historical daily values at Rheinfelden, in Switzerland, have been averaged over a monthly period to better highlight seasonal trends. In this blog post, I’ve chosen to focus on upstream river cycles, which are largely influenced by what’s going on in the Alps. Other sections of the river will be treated in future posts.

The peak in water flow occurs in the spring, when snow from the Alps melts down. In the chart, annual peaks in flow can be seen very clearly. The stream eases through the summer and autumn as snow reservoirs become progressively depleted, even if the melting of hard ice continues to feed the river for some time.

Low water is typically reached in the winter. During the season, precipitation falls as snow at high altitude and can also be stored as ice in glaciers. At lower altitude, in the Jura and the Swiss Plateau, precipitation will typically fall as rain (unless the weather is very cold) and flows directly into rivers. In the chart above, rain is the reason for the small peaks we see in between the large spring peaks.

The seasonal maximum in snow cover tends to happen right before the peak in water flow at Rheinfelden. Abundant snowfall during the winter is necessary to ensure water supplies in the spring. On that count, the 2019-20 winter season has proved disappointing with snow levels below previous years due to mild weather (See blog update from January 2020: Snow levels in the Alps are well below normal – since then, the situation has improved but not materially so).

Seasonality cycles are somewhat irregular, however. The annual peak in water flow is normally in June, but in the last few years it has occurred as early as May and as late as August, depending on A) temperatures in the spring and summer and B) how much snow and ice is stored in the Alps at the end of winter. A warm spring, such as in 2015, can lead to high flows early in the season, but is also likely to result in lower runoff in late summer and in the fall, with knock-on impacts on river navigation and hydropower production.

In some years, such as in 2017 and 2018, one can hardly notice the annual spring peak. In 2017, snow levels were extremely low at the end of winter, but this was compensated by lots of rainfall in the spring and later in the year, hence the lack of an obvious peak. In 2018, snow levels were high at the end of winter, but then weather turned hot from April onwards, ensuring steady snow melt until the end of June. The summer and fall saw record low water levels as there was no more snow left in the Alps and practically no rain.

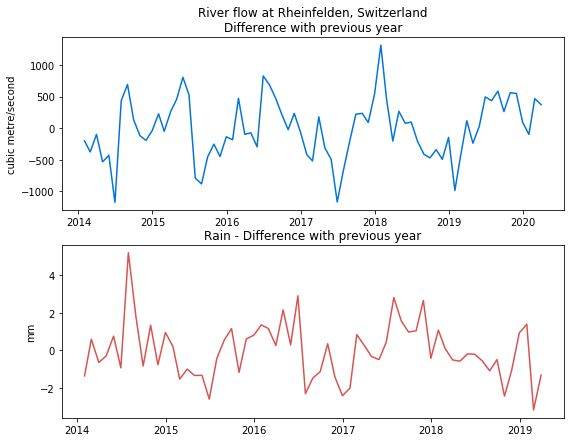

A simple technique to correct seasonality in a time series is to use differencing. We can remove the annual seasonal component by subtracting the average river flow in any given month from the same month in the previous year. This is clearly imperfect, as the peaks and troughs in snow-related water runoff are not the same every year. But this allows us to better understand what’s going on. When comparing the result with monthly rainfall averages, it becomes clear that some of the difference between years is attributable to rain. In the chart below, surges in river flow often run in parallel with increases in rain, though it is by no means the only factor.

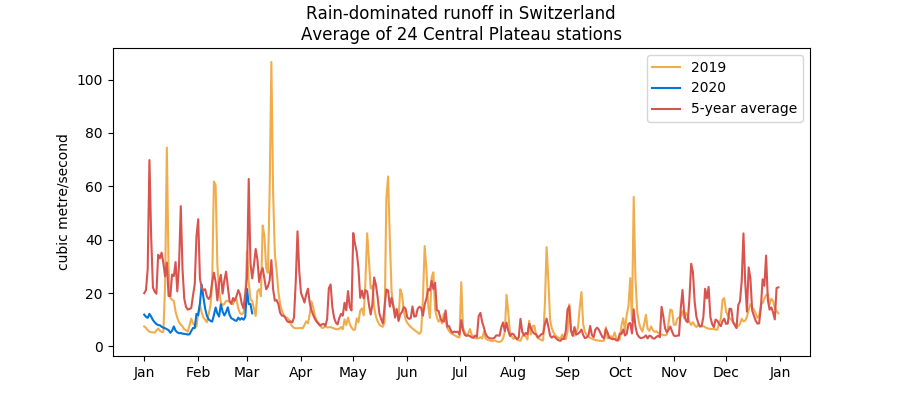

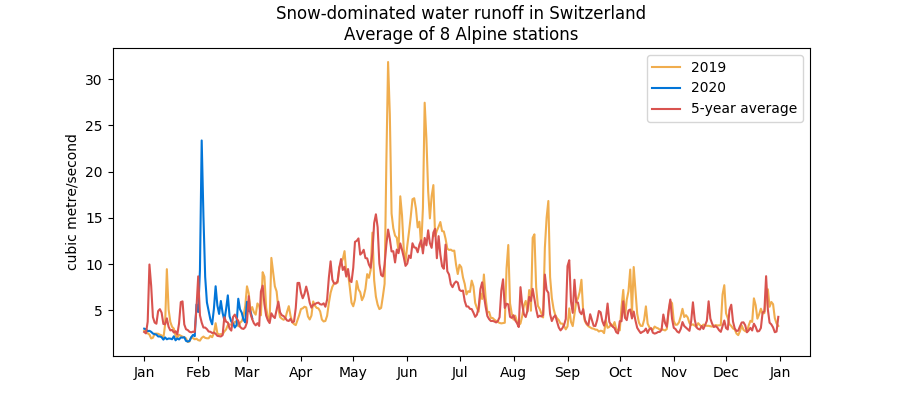

In the 1930s, French hydrologist Maurice Pardé worked on the seasonality of Alpine water runoff and much of what he discovered still holds today. The flow of the Rhine and its major Swiss tributaries (the Aar, the Limmat and the Reuss) can be reconstructed by monitoring the flow of numerous smaller rivers feeding from glaciers, snow peaks or fed by rain. In total, 16 water regimes exist in Switzerland and 12 apply to the Rhine. Rain-dominated runoff shows regular peaks and troughs marked by rain episodes. Flow is slightly elevated in the winter (November to March) relative to the rest of the year.

Snow-dominated runoff is marked by higher flow between April and July, the period when snow melts.

Finally, glacier water runoff starts to rise in late April and peaks in June, slightly later than snow runoff. But it is close to zero during the rest of the year.

We’ve identified a list of around 50 representative river monitoring stations dotted around Switzerland. Once a day, this blog updates their latest flow values, using live data from the BAFU website. This enables us to determine if the current upstream Rhine flow volume is mainly driven by rain or ice/snow melt, and to compare current values for each runoff regime against its respective history.

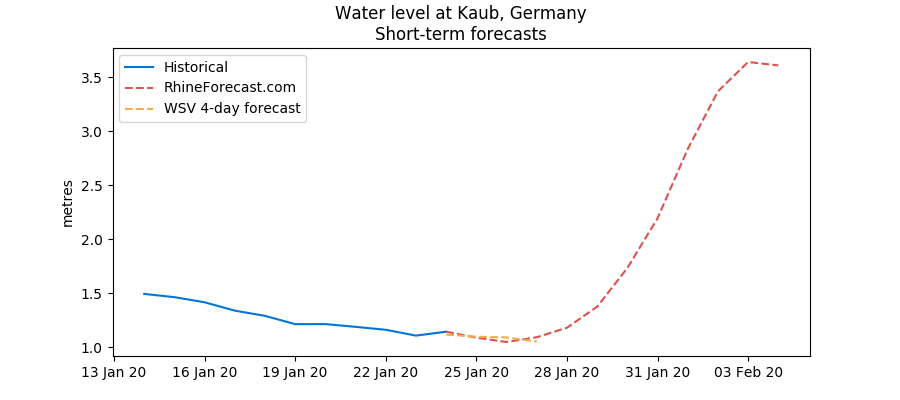

Rhine to breach high water flood mark on 5 February

3 February 2020

Rhine water levels are likely to surpass high water flood marks by Wednesday 5 February or, at the latest, Thursday 6 February. However, for now, it looks like only the first level of high water – set at 4.60 metres in Kaub – will be breached, so the worst disruptions may be avoided.

Rainfall has been intense in the last few days, in turn helping the Rhine and its tributaries swell. In the middle section of the river, the last two days have both seen more than 1 cm of rain (an exceptional level) and the next two are likely to bring the same volume of precipitation.

On top of it, temperatures have been unusually warm, above 10 degrees Celsius on average. This means some snow has melted in the Alps, thus feeding the river further. I know this, because this blog monitors the daily share of rain, snow and glacier melt in upstream water flows.

January was unusually warm and dry, but February is proving very wet so far.

Snow levels in the Alps are well below normal

24 January 2020

Snow levels in the Swiss Alps are below normal for the time of year. It’s not just bad for the ski lovers amongst you but also potentially anyone who depends on the Rhine, as snow provides a crucial reservoir of water for the river in the spring and summer.

Snow thickness at high altitude stations (those situated above 2,000 meters) was 1.6 meters on average on Thursday 23 January, around half last year’s level and well below the five-year average. The situation is concerning because January is normally a month when snow levels build up quickly in the Alps due to a combination of precipitation and cold temperatures. However, this year, snow levels have been mostly stable compared with December amid warm weather.

And, while temperatures in Western Europe have turned noticeably colder over the last couple of days, they are due to warm up going into the end of January and the beginning of February.

It’s too early to write off this year’s snow season, as a cold and wet February could reverse the trend. However, if things continue as they are, a lack of snow is likely to weigh on Rhine water levels in the spring.

Water levels at Kaub, in Western Germany, were just above 1 metre at the time of writing, but are likely to rise significantly in early February if current forecasts of significant rainfall in Germany and Northeast France materialise. On this blog, I expect Kaub levels to surge to around 3 metres by early February, meaning water levels are likely to be plentiful for now.

A tale of two years: 2018 and 2019

4 November 2019

Water levels on the Rhine are at their highest in five years – for the time of year, that is.

October and November are typically low flow months as there is no more snow and little ice left to melt in the Alps following the summer, while rainfall in Continental Europe remains low. In 2018, following an exceptionally hot and dry summer, and an even drier fall, water levels at Kaub reached an historic low of just 30 centimetres, bringing barge traffic on the river to a standstill.

But what a difference a year makes. Kaub levels are currently at 2 metres and are likely to rise to 2.4 metres later this week. There is no concern about barge traffic. The 2019 summer was less hot than in 2018, but more importantly, it was also far more rainy, as shown by statistics I’ve gathered from the German weather service DWD, which are now updated on a daily basis and accessible on this blog.

Average precipitation at 20 weather stations situated close to the river** has been consistently higher in 2019 than in 2018 and, at more than 3 millimetres per day in October 2019, was more than three times as much as during October 2018. As a result, soil moisture along the river is now well above both 2018 levels and the five-year average: we’re now at levels typically reached in late November or early December. This, in turn, provides a reservoir of underground water for the river to continue to flow at robust levels over the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, upstream flow from the Alps has been consistently high in the last few months due to a similar pattern of plentiful rain and strong snow melt in Switzerland. The river’s flow at Rheinfelden***, on the Swiss side of the border, is due to hit 1,300 cubic metres per second on 9 November, its highest in a month and well above the five-year average flow rate.

**I have picked the 20 most relevant stations based on their location in the Rhine basin. They are situated in between Germany’s Rheinfelden and Cologne.

***There are two cities named Rheinfelden, one Swiss and one German.

Rainfall maintains Rhine above 2018 levels

9 August 2019

The situation on the Rhine is not as dire as it looked in July. You can thank rainfall, which has thrown the river a lifeline.

There have been brief but intense episodes of rain over Southern Germany and Switzerland over the last two weeks, which have fed the river. Water levels at the critical hub of Kaub, near many of Germany's industries, rose briefly to 2 metres in late July and look set to rise once again over the next few days.

Rain is forecast in Switzerland on Saturday 9 August and then again in the early part of the week starting Monday 12 August. Water flows at Domat/Ems, in the Swiss canton of Graubünden near the origin of the Rhine, are set to reach 250 cubic metres per second on 13 August, their highest since June, according to the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (BAFU). In Rheinfelden, close to the German border, they'll reach nearly 1,300 cubic metres per second.

This has meant that the Rhine has maintained itself above 2018 levels. This time last year, Kaub levels were already well below 1 metre, but they are now heading above 2 metres.

However, I doubt these episodes of rain will have more than a temporary impact on the river. Soil remains exceptionally dry in southwest Germany, so rain struggles to penetrate deep into the ground. This, in turn, means that the river isn't really fed by underground reserves when it most needs it. This could all change of course with sustained rainfall over Germany and Switzerland, but it's unlikely before the autumn.

Rhine levels drop below 5-year average, likely to fall further

18 July 2019

Water levels on the Rhine are now firmly below historical averages due to hot weather and the seasonal reduction in river flows from the Alps. Levels are likely to reduce even more over the next few days and could break historical lows for the time of year.

For example, Kaub water levels are now below 2 metres - the level at which authorities begin to trigger navigation restrictions - and could fall below 1.5 metre by 21 July, according to Germany's Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration (WSV). Last year, during the drought that lasted for several months, Kaub levels fell to around 1 metre by the end of July.

There is likely to be some rain in Southern Germany on 19 July, but it will be limited and is unlikely to feed the river much. The weather is expected to remain hot (ie, at or above seasonal norms) over the next 10 days in Western Europe.

Meanwhile, river flows in Switzerland have fallen sharply since June's peak in line with seasonal averages. In Rheinfelden, close to the German border, the river currently flows at a little more than 1,000 cubic metres per second, down from 2,000 cubic metres per second a month ago but still more than in 2018.

Kaub water levels to fall below 2-metre threshold on Sunday 7 July

4 July 2019

Water levels at the key German hub of Kaub, situated near many of the country's industries, will fall below 2 metres on Sunday 7 July, according to a forecast by the country's Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration (WSV), due to hot weather.

At that level, authorities begin to trigger navigation restrictions on the river and operators may need to reduce loads in order to sit higher on the water and reduce the risk of running aground.

Water levels in Duisburg, Cologne and Kaub are roughly in line with the five-year average and remain higher than at this time last year. However, the recent hot weather in Western Europe, combined with an extended drought in Germany, mean that water levels are falling quickly. No rainfall is currently forecast over the next 10 days in Western Germany, so the situation could quickly worsen.

Rhine water levels begin summer descent

25 June 2019

River levels on the Rhine are likely to fall sharply over the next few days in line with warm temperatures across Western Europe, which favour water evaporation. Water levels at the key measuring hub of Kaub, situated in Central Germany, will fall from 3 metres currently to 2.6 metres at the end of June, according to Germany’s Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration (WSV). At that point, they will just be 60 centimetres above the 2-metre threshold that triggers navigation restrictions for many ships using the river. This, in turn, could hamper barge movements from the Netherlands for key commodities such as diesel, jet fuel and coal.

For now, water levels in Duisburg, Cologne and Kaub remain above their respective five-year averages due to strong snow melt in the Alps as well as the cold and rainy weather registered during May and the beginning of June. However, the hot weather wave now enveloping much of Western Europe, if it continues, will quickly bring water height below seasonal averages.

The Rhine is still suffering from the exceptional drought that took place during the second half of 2018. The ground around the river is very dry, even after the winter/spring season. This means that the river cannot be fed by ground reservoirs and is thus entirely reliant on rainfall. Without rain over the coming two weeks, German authorities may have no choice but to impose navigation restrictions. The German Drought Monitor, published by Germany's Centre for Environmental Research, currently pegs the ground around the river at the "severe drought" level.

Further upstream, in the Alps, water flows on the Rhine and its major tributaries (the Aare, the Limmat and the Reuss) have fallen for 10-12 days now, indicating that snow melt - which typically occurs between May and July - may have already peaked. River flows are likely to ease over the coming 9 days.

This web app seeks to gather data on water levels from several sources, including Germany’s WSV and the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment, and to present them in a digestible format. The Rhine is Europe’s lifeblood. For centuries it has been used as one of the main arteries for shipping goods into Germany, France, Switzerland and Central Europe. However, with climate change, water levels on the river are likely to become more variable.